According to a report just published by the forecasting company EvaluatePharma, by 2014 seven of the top 10 drugs are expected to be biotech in origin, compared with five in 2008 and just one in 2000. Biotech medicines will also account for half of the top 100 drugs in 2014, compared with less than 30% in 2008.

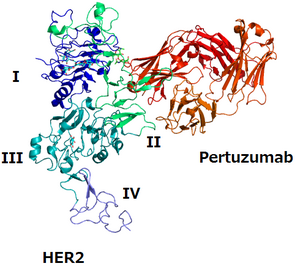

EvaluatePharma predicts that the leading product in five years' time, will be Roche's anticancer monoclonal antibody (MAb), Avastin (bevacizumab), which by 2012 will have taken the top spot currently held by Pfizer's blockbuster cholesterol-lowerer Lipitor (atorvastatin). Anticancer antibodies will probably become the most valuable therapeutic class of drug, at least partly justifying Roche's recent move to acquire Genentech outright, it says.

The increasing dominance of biotech drugs reflects their importance as growth drivers for the industry over the coming years, when many big-selling small-molecule medicines like Lipitor are set to lose their patent protection. But it also brings into sharper focus a looming challenge for the originator biotech industry: the proposed US legislation on biosimilars. As pointed out by Mr Ian Schofield in Scrip News, it’s no wonder biotech companies in the US are fighting so hard for a long data exclusivity period to delay competition from biosimilars.

Biosimilar competition

A number of bills implementing a biosimilars pathway are currently going through US Congress, and all include some form of data exclusivity. Originator companies are keen to ensure this exclusivity is as extensive as possible, and are pressing for at least 12 and possibly 14 years.

One of the bills, sponsored by Democrat Anna Eshoo, suggests 12 years of exclusivity and is favoured by the innovator industry. Another, sponsored by Democrat Henry Waxman, suggests five years and, understandably, is backed by generics firms. So what will be the outcome? It is difficult to say at this time because the bills are still at the committee stage and there is a long way to go yet before any legislation is approved.

However, politically speaking this may not be the best time to press for a data exclusivity period that will prevent biosimilar competition for up to 14 years from the date of the originator's approval. The whole idea of biosimilars is to save money on the drugs bill, and healthcare payers, whether public or private, fear the consequences if cheaper alternatives to effective but costly biotech drugs are not made available at some point, preferably sooner than later.

President Barack Obama is expecting biosimilars to generate huge savings, which he expects to use in funding his ambitious healthcare reforms. 12–14 years of data exclusivity period would hardly seem to fit this scenario.

Indeed, in his fiscal 2010 budget proposal, Mr Obama called for an exclusivity period that was ‘generally consistent’ with the principles in the 1984 Hatch/Waxman Act, which offers new chemical entities a five-year exclusivity period. Addressing the American Medical Association on Monday, 15 June 2009, the President urged doctors to support the principle of a biosimilars pathway, claiming it would save ‘billions of dollars’.

Nor can the biotech industry take any comfort from a recent report from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which has looked into the matter and concluded that 12–14 years is not necessary to sustain biotech innovation, and that biotech firms already have plenty of product protection through patents and competitive pricing.

So why are there such divergent opinions as to the length of data exclusivity needed to protect innovation? And why should biologicals have more protection than chemical drugs?

After all, in Europe, which has had a biosimilars pathway in place for some time now, the pharmaceutical legislation makes no such distinction; all new products, whether chemical or biological, enjoy an eight-year data exclusivity period followed by two years of market protection (although it has to be said that this was a compromise reached after years of bargaining).

Patent protection gap

According to the US Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO), in proposing a short data exclusivity period, both the FTC and the Waxman bill ignore what it calls the ‘patent protection gap’.

BIO argues that the Waxman bill gives a ‘very broad and undefined view’ of similarity, and while it provides for the approval of a product that is highly similar structurally and has the same mechanism of action, dosage form and strength as the innovator, it also allows ‘any or all’ of these requirements to be waived.

Biosimilar products could therefore be approved that were in fact ‘quite dissimilar’ to the innovator product, BIO says, adding that this raises ‘substantial questions’ about the effectiveness of innovator patent protection – a fact that is completely ignored by the FTC report.

BIO also says that patent protection for large-molecule biologics is often narrower and easier to ‘design around’ compared with chemical products, and that the trend is increasingly towards narrow biotech patents.

Patent protection would therefore be rather unpredictable, and this is why 12–14 years of data exclusivity period is needed, the industry asserts.

But still, the gap between five and 14 years is a pretty wide one, and a 14-year data exclusivity period would seem to have no parallel elsewhere. And anyway, where did the 12–14 years figure come from in the first place? Why not seven years, or 15?

To support its position, BIO cites a peer-reviewed study published last year by Professor Henry Grabowski of Duke University, Durnham, NC, USA, which found that innovators would not be able to recoup their investment in a reasonable period of time without 12–14 years of data exclusivity. This figure was founded on the assertion that the ‘break-even’ point – the number of years required to recoup costs and offer investors the expected rate of return – was between 12.9 and 16.2 years.

But this assumption has been contested by Mr Alex Brill, a Principal at Matrix Global Advisors and a former Chief Economist with the House Ways and Means Committee. In a white paper released in November last year, he said that the break-even point was actually much shorter – nearer to nine years – and that taking account of profits earned after biosimilar competition arrived, the optimal data exclusivity period would be seven years.

It is worth asking whether industry should be setting so much store by the length of the data exclusivity period. In view of the current political focus on levels of healthcare spending, should it be pressing for lengthy extensions for what are very costly products?

As noted above, EU legislation offers the same data exclusivity period to all new medicines, whether chemical or biological. Moreover, the EU approval pathway does appear to be producing ‘biosimilar’ medicines, and the ‘patent protection gap’ does not seem to be a big issue.

If the problem in the US really is the ‘patent gap’ and the fear that biosimilars firms might use the abbreviated pathway to gain approval for products that circumvent patents, industry might therefore be well advised to concentrate instead on pressing for legislation that does not allow the approval of ‘biodissimilars’ in the first place.

It might also need to give ground on the data exclusivity period. Industry wants 14 years, and Waxman says five. The Brill analysis suggests seven. So why not compromise at, say, eight or 10 years, Ian Schofield stated in Scrip News. Then, in the biotech segment at least, the US would be pretty much in line with Europe. And with globalisation and international harmonisation very much in fashion, would that be such a bad thing, he argued.

BIO support

BioWorld Today recently reported that US Representative Ms Eshoo demands a compromise on the data exclusivity period for biosimilars. During a follow-on biologics (FOBs) forum she said that her biosimilars bill (demanding 12–14 years data exclusivity) is now backed by more than 100 members of the US House, while Waxman’s competing bill (demanding five years data exclusivity) has just over a dozen co-sponsors.

Ms Eshoo insisted that her bill does more to protect patient safety than Waxman’s bill and that her legislation provides protection for intellectual property rights of third parties, such as universities and medical centres. Furthermore, her bill is the only one endorsed by the American Association of Universities, the National Venture Capital Association and BIO.

Ms Eshoo said that getting more than 100 congressional co-sponsors to sign her bill has been a “heavy lift”, given the complexities involved in explaining biologicals, let alone their differences to FOBs, to lawmakers unfamiliar with those products or the science behind them. “This broad support is extremely encouraging,” she said.

Source: BioWorld Today, EvaluatePharma, Scrip

0

0

Post your comment