Widespread therapeutic use of biological pharmaceutical products appears to be inevitable. Nevertheless, the law governing approval of biosimilar products in the US is still not in place. The size of the biologicals market and impending patent expiries, however, are making approval of a practical pathway for biosimilars more urgent.

While small molecule drugs are ideal for generics replication, biological drugs are not so simple.

An application filed by a generic pharmaceutical manufacturer under the Hatch-Waxman Act must demonstrate that the active ingredient of the generic drug is the same as that of a drug that has been previously approved by the FDA, listed in the Orange Book, and that the proposed generic product is bioequivalent to the Orange Book listed product.

Doctors and patients can expect that generics will have the same properties, the same efficacy, and the same safety characteristics as the originator product.

In contrast, biological drugs are usually large, complex molecular structures derived from or produced through a living organism, making them very difficult to replicate. Even for the originator biological, small changes in the manufacturing process can cause changes in the final product, making things even more complicated for potential biosimilars.

Even if a biosimilar is proven to be safe and effective, it is likely to still have different properties than the originator product.

Today, more than 150 biologicals have been approved for marketing in the US. Only a few of these, such as Sandoz’s Omnitrope (somatropin), can be characterised as biosimilars. Nevertheless, in 2009, the top 20 classes of biological pharmaceutical products generated sales of some US$91.78 billion, making many of them ‘blockbusters’ [1].

The market for biologicals is also expected to grow at twice the rate of the market for small molecule drugs, which many Big Pharma companies are hoping will somewhat offset the losses due to the infamous patent cliff of 2010-2015.

It is therefore expected that the focus of many pharmaceutical companies will move towards the more lucrative biologicals. There are reported to be more than 370 biopharmaceutical drug products and vaccines currently in clinical trials targeting more than 200 diseases including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, AIDS, and arthritis [1].

In the next decade, if not sooner, biologicals are expected to become the most important economic and therapeutic component of the pharmaceutical market. According to one estimate, by 2016 eight of the top 10 pharmaceutical products will be monoclonal antibodies or recombinant products.

These developments and the substantial gains to be made from copying these blockbusters may also lead to more rapid market entry of biosimilars, despite the significant costs associated with developing and marketing a biosimilar compared to a generic of a small molecule drug.

The costs of developing a typical biosimilar have been estimated to be more than US$100 million, with it taking five to six years to develop—much more than a small molecule generic—reflecting the complexity of the molecules in question [2].

While in Europe the regulatory frameworks for biosimilars are largely established, the US, on the other hand, is lagging some way behind. One of the main problems is that the US, although it now has a legal pathway (with the approval of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation [BPCI] Act, which was signed into law on 23 March 2010 by President Barack Obama), does not yet have a practical pathway with guidance defined by the FDA.

Biologicals exclusivity

The US is also still arguing about the period of exclusivity that will be granted to originator biologicals, with a 12-year period being allowed for in the BPCI, but President Obama in his 2012 budget proposal suggesting a 7-year period in order to boost competition [3].

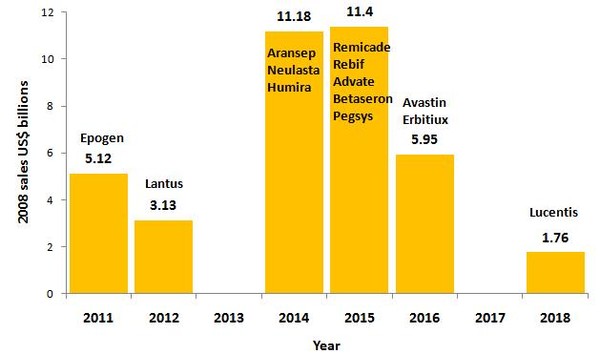

Even with a 12-year period, more than US$20 billion-worth of biological drugs has already lost market exclusivity between 2008 and 2010, with a further US$38 billion expected to be open to competition from biosimilars by 2018. Some of the biggest blockbusters, such as Enbrel (etanercept), Epogen (epoetin alfa) and Rituxan (rituximab), each with more than US$5% billion in 2008 sales, are already at risk from competition from biosimilars, see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Loss of market exclusivity for biologicals 2011-2018

Source: Ohly and Patel, Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice

Related articles

Partnerships will drive biosimilar development

Exclusivity for biological drugs in the US: what now

References

1. Ohly DC, Patel SK. There is no Orange Book: the coming wave of biological therapeutics. Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice. 16 May 2011. doi:10.1093/jiplp/jpr048

2. GaBI Online - Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Partnerships will drive biosimilar development. [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2011 June 30]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/Partnerships-will-drive-biosimilar-development

3. GaBI Online - Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Exclusivity for biologic drugs in the US: what now? [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2011 June 30]. Available from: www.gabionline.net/Policies-Legislation/Exclusivity-for-biological-drugs-in-the-US-what-now

0

0

Post your comment