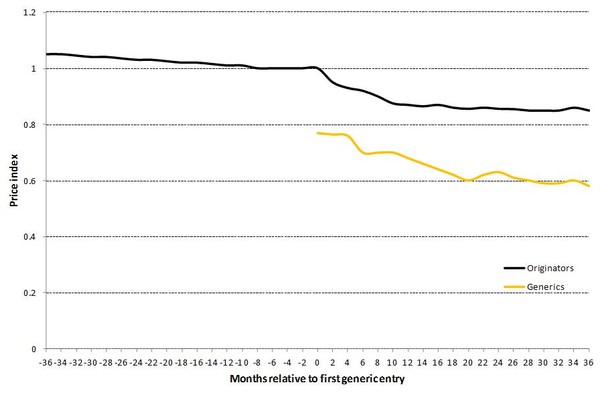

Once a medicine marketed by the originator company is no longer protected by patents or other exclusive rights, generics companies can enter the market with a medicine that is equivalent, in terms of efficacy, safety, and quality, to the original. This lowers prices and enhances access to affordable treatments. The generic medicines are always cheaper than the originator brands. In addition, the prices of originator products after two years of generics competition are around 10% lower than at the time of generics entry [1], see Figure 1.

How originator companies delay generic medicines

Home/Reports

|

Posted 16/12/2011

0

Post your comment

0

Post your comment

This is the second of three articles on the EU pharmaceutical sector enquiry.

Figure 1: Development of originator and generics price indices for medicines with generics entry

Note: Six months before loss of exclusivity, the originator price index is set equal to one.

Source: Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Final Report (partially based on IMS data)

Generics entry does not just affect price. It also affects companies' market shares. Generics companies attain about 30% market share in volumes at the end of the first year and 45% after two years. Further, it appears that the decrease in price levels allows the use of the medicines concerned to increase, as can be observed by the growth in volume sales after generics entry.

Tool-box of strategies used by originator companies

The sector inquiry found that originator companies use a variety of strategies and instruments to maintain revenue streams from their medicines, in particular blockbusters, for as long as possible.

These practices delay generics entry and lead to healthcare systems and consumers paying more than they would otherwise have done for medicines. The ‘tool-box’ mentioned by the EU enquiry includes:

- strategic patenting

- patent litigation [1]

- patent settlements [1]

- interventions before national regulatory authorities

- life-cycle strategies for follow-on products.

Strategic patenting

Many pharmaceuticals enjoy prolonged patent protection because innovators have obtained separate patents on the diverse formulations and other aspects of the product. This results in so-called ‘patent clusters’ covering the composition, presentation, manufacturing process, dosing and even the colour of the pharmaceutical. Generics competitors are faced with the decision of whether they should wait until all patents have expired before applying for market authorisation, or whether they should be ready to face the risk of patent infringement litigation and consider market entry with a substitute to the originator’s first formulation of the product.

The Commission further identified the practice of voluntarily filling ‘divisional’ patents. The final report summarised its findings with respect to patent clusters and divisionals as follows: ‘The intended effects of both patenting strategies as analysed above are identical: in some case[s] both patent clusters and divisionals seemingly serve to prevent or delay generic entry. While this, during the period of exclusivity, is generally in line with the underlying objectives of patent systems, it may in certain cases only be aimed at excluding competition and not at safeguarding a viable commercial development of own innovation covered by the clusters’ [paragraph 523, Final Report]. The European Patent Office concurred and in 2009 tightened up the conditions under which a divisional patent can be requested.

Interventions before national regulatory authorities

Until recently, generics manufacturers were granted marketing authorisation under an abridged procedure, provided the reference product was authorised in the EU and was marketed in the Member States for which the marketing authorisation was requested. By changing the market authorisation from one formulation to another—a practice known as ‘product hopping’—and/or changing the pricing and reimbursement status, originator firms made it difficult for generics companies to apply for marketing authorisation. These practices delayed the introduction of the generic product by on average four months. The Commission characterised this as an abuse under Article 102 and started legal proceedings against AstraZeneca, alleging the company’s underlying intent to defy generics competition.

Life-cycle strategies for follow-on products

In a number of cases, originator companies try to switch patients from medicines facing imminent loss of exclusivity to a so-called second generation, or follow-on, medicine. The findings of the sector inquiry suggest that originator companies launched such follow-on medicines in relation to 40% of the medicines in the sample selected for in-depth investigation that had lost exclusivity between 2000 and 2007.

On average, the launch took place one year and five months before loss of exclusivity of the first generation medicine. In some cases, the first medicine was withdrawn from the market some months after the launch of the second generation medicine. If originator companies succeed in switching patients by that point, the probability that generics companies will be able to gain a significant share of the market decreases significantly. If, on the other hand, generics companies enter the market before the patients are switched, originator companies have difficulty persuading doctors to prescribe their second generation medicine and/or to obtain a high price for it.

Other strategies

In order to prolong the life cycle of their medicines, originator companies frequently combine two or more instruments from the ‘tool box’ described above. Other practices may include secondary patenting and defensive patenting. Secondary patents are patents relating to products containing active ingredients already covered by a primary patent or covering new production processes for the production of active ingredients already covered by a primary patent. According to the preliminary report defensive patenting arises when firms patent an invention which they have no interest in developing and bringing to the market. The aim is to keep other originator companies from further developing a specific invention and bringing it to the market.

Conclusion

The tension between intellectual property rights and competition law, which can be seen in many industries, has also surfaced in the pharmaceutical sector. Analysts conclude that competition law needs to evolve if it is to accommodate and address legitimate business concerns of the innovative sector. Under the current rules, co-operation between the innovative and generics industry will often prove difficult.

The Commission has been criticised by the industry for not providing meaningful guidance. It replied in paragraph 1245, final report that it refuses to ‘provide guidance on whether [the] agreements can be considered compatible or incompatible with EC competition law [as] [s]uch an assessment would require in-depth analysis of the individual agreement, taking the factual, economic and legal background into account’. The policy of bringing a minimum of lawsuits but deterring malpractice by other means has been successful in this area of competition.

Related articles

Problematic pharma patent settlements decrease in the EU

EU investigation tackles pay-for-delay

European Commission investigates Johnson & Johnson and Novartis over delaying generics

Problematic patent settlements in EU on the decrease

European Commission to investigate patent settlements again

Reference

1. GaBI Online - Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. EU investigation tackles pay-for-delay [www.gabionline.net]. Mol, Belgium: Pro Pharma Communications International; [cited 2011 December 16]. Available from: http://gabionline.net/Reports/EU-investigation-tackles-pay-for-delay

Source: European Commission

Guidelines

US guidance to remove biosimilar comparative efficacy studies

New guidance for biologicals in Pakistan and Hong Kong’s independent drug regulatory authority

Policies & Legislation

EU accepts results from FDA GMP inspections for sites outside the US

WHO to remove animal tests and establish 17 reference standards for biologicals

EU steps closer to the ‘tailored approach’ for biosimilars development

Home/Reports Posted 21/11/2025

Advancing biologicals regulation in Argentina: from registration to global harmonization

Home/Reports Posted 10/10/2025

The best selling biotechnology drugs of 2008: the next biosimilars targets

Post your comment